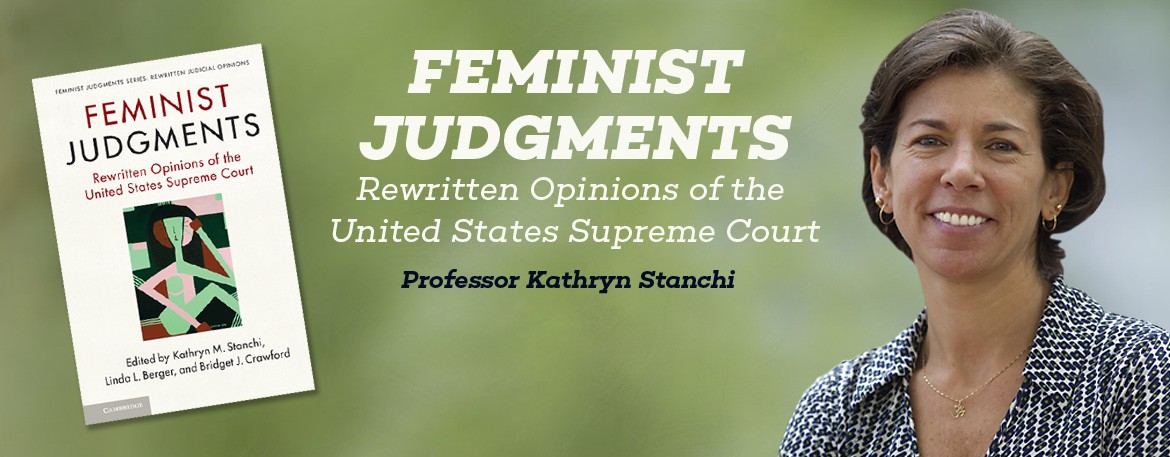

Professor Kathy Stanchi returns to discuss her latest book, Feminist Judgments: Rewritten Opinions of the United States Supreme Court, as it relates to some current events and conversations. Read the previous Q&A here.

Temple Law School (TLS): Tell us about the project. What does it do, and what are its goals? Why is the project important?

Kathy Stanchi (KS): The Feminist Judgments project seeks to write the feminist resistance in law by rewriting key judicial decisions using feminist reasoning. Our first volume takes on 25 SCOTUS decisions related to gender. The authors of those rewritten decisions were required to situate themselves as a Justice at the time of the original decision – they could use only the record of the case and the legal precedent in place at the time. Like any judge, they brought their own perspective, experiences and interpretation to the case. However, unlike most judges, the perspective of our authors was feminist.

The goal was to show that law is so much more than the calling of “balls and strikes” or the application of firm black-letter rules. It is a deeply cultural process in which life experience and perspective matter. We hoped that requiring our authors to use only the record of the case and existing legal precedent would prove our hypothesis that a feminist jurisprudence was and is possible with the Constitution and statutes that exist right now – and we were right. Every opinion in the book shows how the court could have reached a different kind of decision just by having judges with a different view of the law in place at the time.

TLS: “Feminist” can mean different things to different people, and it is often considered a divisive word. Can you define or explain the feminism of the book?

KS: The feminism of the book is inclusive and celebrates diversity. It certainly encompasses the quest for women’s equality, but is bigger and broader than that. It endorses justice for all people, particularly those historically marginalized because of gender, sexuality, ethnicity, race or other characteristics. That means that white feminists have to confront their race privilege and straight feminists have to confront their heteronormative ideas. It means wealthy feminists have to acknowledge how their social class might skew their thinking. It is also inclusive of men. Many cases in the book consider how some laws, like those that rely on sex stereotyping, can harm men as much as, if not more so, than women. I see feminism is a process of questioning and probing to the end of fairness and justice.

TLS: What do you say to those who might regard the project as merely an academic exercise?

KS: I’d say they are wrong! Feminist Judgments is a highly pragmatic inquiry fusing law practice with feminism. We aren’t writing law review articles. We are writing judicial decisions, bringing feminism to the practice of law, and essentially writing a script for feminist lawyers and judges. I see it as a deeply practical but radical act of legal writing. The project’s practical methodology provides striking proof that the outcomes of these cases were not in any way inevitable or mandated by the existing rules – and perhaps more important, that the law that developed from these decisions did not have to develop the way it did.

TLS: Does Feminist Judgments take a position on judicial objectivity?

KS: I think a main goal of the book was to add to the mounting evidence that indicates that what the law reveres as objectivity is a myth. We all bring our life experiences to work with us, and lawmakers are no exception. Every lawmaker, including judges, comes to the law with a perspective that is a combination of life experience, gender, race, class, religion, disability, language and sexuality, among other qualities.

There’s a famous story about Lewis F. Powell who was called upon to help a young employee at his law firm whose girlfriend had bled to death after trying to give herself an abortion. Powell, a son of a patrician Southern family, was an unlikely but unwavering supporter of Roe and abortion rights when he served on the Court. On the other hand, Powell was the deciding vote in Bowers, which held that the Constitution permits the criminalization of homosexual sex. At the time of Bowers, Powell had never met an openly gay person. The Powell stories show us how important experience and perspective are to judicial decision-making.

Feminist Judgments takes the next step. If experience and perspective are a part of judicial decision-making, then it follows that to achieve true justice, we need a judiciary that is diverse in experience and perspective. Feminist Judgments shows us that diversity matters, not just as a moral imperative, but because it will make a difference in the law.

TLS: Along those lines, the President is tasked not only with filling the vacant Supreme Court seat, but also hundreds of federal judge seats. Does Feminist Judgments show us anything about what is at stake in that process?

KS: I don’t think it is an overstatement to say that fairness and justice are at stake. Our federal judiciary has been and continues to be overwhelmingly drawn from a very narrow swath of the population – well over 50{78ecce420c77cf1db311302f5b6e37cdb1436b302b8829c31daeba597410ad34} of the federal judiciary is white and male. Wholly apart from the optics – that it looks like we don’t have a federal justice system that fairly represents the population – this means that our judges have a narrow set of life experiences and perspectives – and that includes both liberal and conservative judges. Many of our judges, for example, may never have been searched by a police officer, or stopped and frisked without cause – or even known anyone who has. Look at Justice Sotomayor’s dissent in Utah v. Strieff in which she highlights both the problem of racial profiling and the invasiveness of a police “stop.” That’s a valuable perspective and it has been missing all these years from the law of the Fourth Amendment. Feminist Judgments stands as a testament to the importance of diversity in judicial appointments, of getting a wide variety of perspectives and experiences on the bench.

This is particularly important in the current political climate because of the importance of the judiciary as a check on presidential power. We have a chief executive who has a taste for unilateral power – he signed 34 executive actions in his first 45 days in office. The judiciary is going to be critical as a check on the President’s actions. We’ve seen that check already beginning in the travel ban cases. In this climate, the diversity point is even more essential.

Feminist Judgments: Rewritten Opinions of the United States Supreme Court is available now. For more information about the project, visit their website or follow @usfemjudgments on Twitter.